Learning the C Programming Language

Part Two: Types

This post follows on from my first post about the C programming language, and is the second in a series of posts about learning C

C has types - what does that mean? This post is going to focus on types and the role they perform in C. We’re going to show how they’re used but, more importantly, we’re going to look at why they’re used.

All the types!

A type in C is a type of data. For instance, if you want to use a whole number

in C you can use an int, whereas if you want to use a decimal number you would

need a different type of data, say a float.

The first temptation to watch out for, definitely from the Ruby side of my brain, is to think of types as being like classes. Types are ways of storing data in a computer (as we’ll make clear), and not objects with methods, inheritance, attributes and all the other object oriented stuff. Forget about classes.

So to store an integer C has int. But it also has long, which will store

a bigger integer, and, on top of that we have long long, which will store

a really big integer. And if you just happen to know that the number you want

to store is really, really big but will never be negative, you can go so far

as to use the type unsigned long long.

This may all sound a little ridiculous from the point of view of a Rubyist or

a JavaScripter - I mean, I can see why maybe a float is different to an int,

but why do I need all these different ways to talk about integers?

The reason cuts to the heart of what a type system is for, and why C is a lower level programming language than Ruby and JavaScript.

Types for the memory

In C when we declare a variable we declare it with its type:

int my_number;

We can then assign a value to it:

int my_number;

my_number = 5;

In Ruby, you’d just need the second line, and in JavaScript it would be the same

but int would be replaced with var.1

So, what’s going on under the hood of your computer when you say “OK computer, let’s have a variable”?

This is the bit where I remember the video of the American politician explaining that the internet is just a series of tubes.2 Well, I’m about to be just as reductivist and say that your computer’s memory is ‘just’ a big long line of ones and zeroes.

So Matrix.

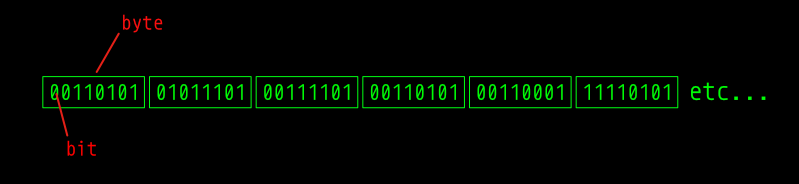

Each one of these ones and zeroes is called a bit (Binary DigIT - geddit?). And eight of those in a row is called a byte (no idea, you look it up).3 Byte is a good level of abstraction to work from for C, so let’s replace our image of a very long list of zeroes and ones with a very long row of boxes, each box holding a byte of information.

Less Matrix, but we’re cool, right?

Why we have types

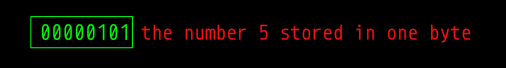

So now we need to do something with this memory - write programs! Ok, more specifically, we need to keep hold of an integer. And we can do this by reserving a specific portion of that very long row of boxes to keep the number in. But how many boxes do we need to do that? Well, basic maths tells us that a single byte could hold any number from 0 up to 255 as long as it’s positive.4 Cool - so now we can keep hold of the number 5.

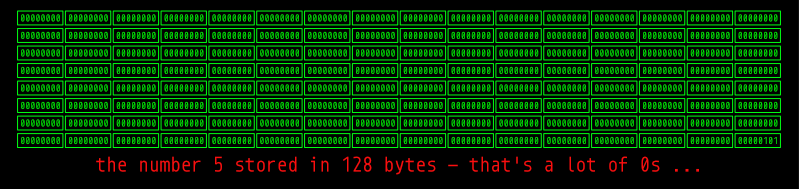

But we might need to store much bigger numbers - what if we added 255 to our that variable, we’d not have enough space to store the number 260. So maybe we should reserve more bytes in memory to hold that number. How many? I don’t know, maybe 128 of them, just to be safe.

But isn’t that terribly inefficient? We’d just be reserving a lot of bytes

which would always be 0 if we never kept a number bigger than 20. I mean,

this is C - the year is 1971, the most memory we’re going to have available is

64KB. We don’t want to run out of memory messing around with piddly little

positive integers… how much space do we need to allocate to store a number?

And that’s why we have different types for different magnitudes of integer. For

small numbers there’s things like char (a single byte) and int, and for

bigger numbers we’ve got the mighty long long and unsigned long long.

The type of a variable is the space reserved for it in your computer’s memory.5 C offers us control over memory allocation, at the price of us actually having to care about memory.

For instance, char which is good for storing information about a single ASCII

characters (more about them later). But if we need to keep hold of a number

bigger than 255, we can go with int, which is guaranteed to store a number

between −32767 to 32767, which is two bytes.

We say “guaranteed”, because a system’s implementation of C could allocate more

memory to an int, so the C standard tells us the maximum number a type can

definitely store. In reality it’s larger - on my Macbook Pro the maximum size of

an int is in fact between -2147483648 and 2147483647 - four bytes in fact.

Integer overflow

Let’s try some of this stuff out - here’s a fun program.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int int_number;

int_number = 2000000000;

printf("int_number: %d\n", int_number);

int_number = int_number + 2000000000;

printf("int_number + 2000000000: %d\n", int_number);

}

Here we’ve got the main() function again, which will runs on execution. We’re

declaring a variable of type int called int_number on line 4 and assigning

it the value of two billion on line 5. Then we’re printing it out - printf()

can take a format string as its first argument, allowing later arguments to be

interpolated into the string - %d is the placeholder for an int to be

inserted, so the value of int_number is printed instead of the &d in the

string.

Then we reassign int_number to the value of int_number plus another two

billion. And finally we print out the value of int_number again.

To compile and run it take a look at the first post in this series. Try it now and see what you get.

Something pretty odd, right? Maybe it’ll be different on your computer but here for me the result of 2000000000 + 200000000 is -294967296. Which is just wrong.

What happened? Well we just experienced integer overflow, where C quite happily adds two numbers together and stores them in a variable, but if the type of the variable isn’t big enough to hold the new number C will just store as many bits as it can in the space it’s got. Look, try this variation:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int int_number;

int_number = 2147483647;

printf("int_number: %d\n", int_number);

int_number = int_number + 1;

printf("int_number + 2000000000: %d\n", int_number);

}

You should get -2147483648, not 2147483648.

Integer overflow is like the moment when all the numbers on your car’s odometer

are all 9s, and then they all roll over at once to all the 0s - you’ve run out

of space to represent the new number with digits you’re using. And for ‘digits’

in our example read ‘bits’ - 1111111111111111 becomes 0000000000000000,

which is the representation of -2147483648 in binary.6

Fixing integer overflow

To solve this problem we need a ~bigger boat~ larger type to store our number

in, which is as easy as changing an int to a unsigned long long:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

unsigned long long int_number;

int_number = 2000000000;

printf("int_number: %d\n", int_number);

int_number = int_number + 2000000000;

printf("int_number + 2000000000: %d\n", int_number);

}

We should now be getting a nice round four billion.

Types in Ruby and JavaScript

Ruby and JavaScript also have types - but we just don’t get to see them as often and they’re not as granular. JavaScript numbers always take up 8 bytes - big enough to handle most numbers - and Ruby just switches the class of a number as it grows between classes like Fixnum and Bignum. These are both good solutions, and take away the headache of having to think about the correct type to use to represent an integer, but also lack the freedom for us to manage memory directly.

Practically speaking…

In practice when I write C, I start with using ints, wait until I see errors

that are due to integer oveflow, and then find and replace to change the ints

to long long or unsigned long long. In practice, on my highly specced modern

computer, I’m not too worried about tinkering with how much memory I’m using for

my toy C programs.

But it’s nice to know I can.

- Or

letorconstor whatever the new flavour of the month is. Or you could do it in a single line,var number = 5, which some versions of C will also let you do:int number = 5 - The late senator Ted Stevens

- Worth noting that the size of a byte was only fixed when IBM decided it would be 8 bits. Maybe take a look at this.

- Eight ones,

11111111, in binary is 255 in decimal. - This may be a contentious statement. Here I’m refering to type as early programmers would have understood the idea of a type of data, rather than the types of type theory, based on Bertrand Russell’s solution to the set theoretic paradoxes, which was later brought in to computer science by way of Alonzo Church and languages like ML and which functional programmers tend to wax lyrical about in languages like Scala. Take a look at this blog post and this short post.

- If you want to know why this is, take a look at some articles on Two’s Complement. This one is pretty good too.

unsignedtypes don’t have to worry about this and so can consequently store larger, non-negative integers.