(Basic) Lazy Evaluation and Memoization in JavaScript

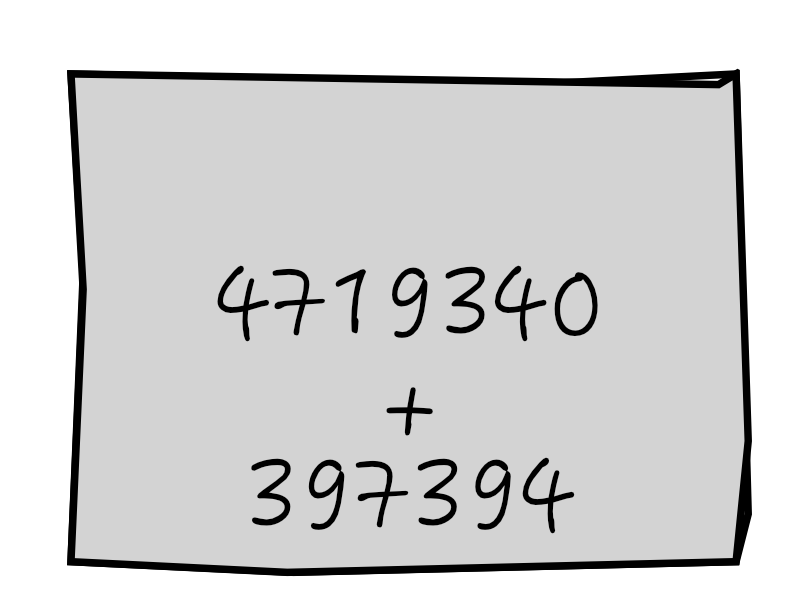

Calculation takes time and effort. If I needed to know what, say

4719340 + 397394

was (and I didn’t have a calculator), it would take a few minutes to work out.

Right now, I don’t need to know. Maybe I’ll never need to know. I could put

those two numbers and the + sign on a piece of paper and stick it in my

pocket.

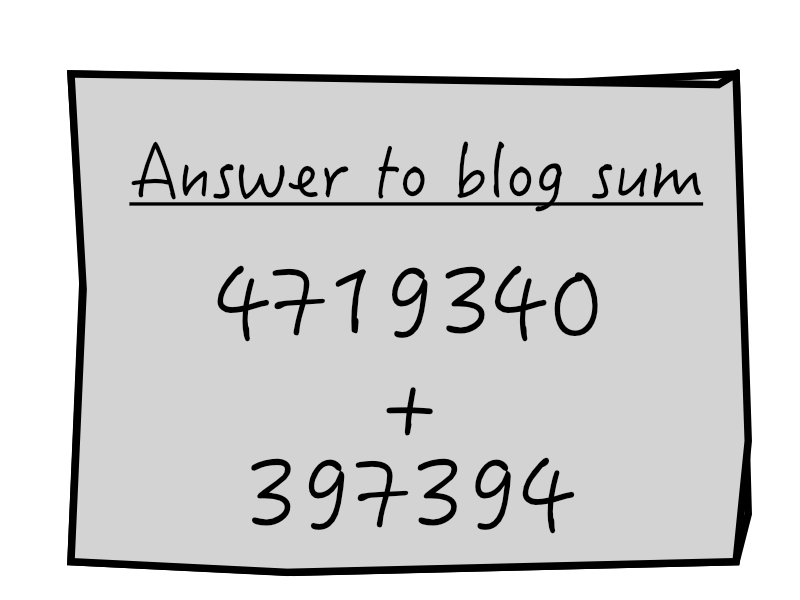

If I ever wanted to know the answer, I could get the paper out and do the maths. I should write ‘Answer to silly blog sum’ on the top of the paper.

Now I know what the sum is there for. And why I’m carrying a piece of paper around.

That’s lazy evaluation - holding on to an expression and only evaluating it when you need it. It pairs neatly with memoization - keeping the results of evaluated expressions in memory so that you don’t have to evaluate them every time you need their result.

(Which figures as, if I ever do work out what 4719340 + 397394 is, I never

want to work it out again. Ever.)

Let’s take a look at doing some lazy evaluation in JavaScript - in other languages, such as Clojure, we get a lot of this baked in, but in JavaScript there’s some work to do. Let’s take a simple function:

function add (a, b) {

return a + b;

}

And we’d like to make that function lazy - with another function, naturally. Something like:

var addThisLater = lazyEval( add, 4, 5 );

addThisLater() //=> 9

lazyEval() takes a function name, some more arguments, and returns a function

that, when it evaluates, returns the result of evaluating the passed in function

with the other arguments.

So far so good - but what needs to be returned from lazyEval() to make it work as

described above? As it turns out, not that much:

function lazyEval (fn) {

return fn.bind.apply(fn, arguments);

}

And this is where things get exciting. We’ve seen bind() before, so

let’s take a look at apply(), what happens when we chain it with bind(), and

what’s happening with arguments keyword.

apply()

apply() is pretty simple - it’s a method that all functions have. It takes

two arguments. When its evaluated it returns the result of evaluating the

function within the scope of the first argument (just like bind()). The second

argument is an array (or an array-like object - that’s important) of arguments

for the function to be evaluated with. Which all sounds scary, but if I do this:

add.apply(this, [ 1, 2 ]) //=> 3

I hope that begins to makes more sense. Now let’s take a closer look at arguments.

arguments and Argument Binding

arguments is an array-like object (it lacks a number of methods that arrays

have) which contains, unsurprisingly, all of the arguments passed to the current

function you’re in the scope of - even ones not bound to a variable.

JavaScript functions, unlike some other languages, can take as many parameters as you like. Which means that this:

add(1, 2) //=> 3

works just like this:

add(1, 2, 'peace', ['love'], { and: 'understanding' }) //=> 3

add() binds its first two arguments to a and b. Those extra arguments get

ignored - add() just goes on adding as usual. But that does not mean that

those arguments go nowhere. They’re still available to the function in the

arguments array array-like object.

Look, try this:

function echo () {

return arguments

}

echo(1) //=> { 0: 1 }

echo('peace', ['love'], { and: 'understanding' })

//=> { '0': 'peace','1': [ 'love' ], '2': { and: 'understanding' } }

echo('faith', 'hope', 'charity')[2] //=> 'charity'

OK, back on track. When apply(fn, arguments) is evaluated, it is passing the

arguments fn, 4, 5 along to the function that apply() is being called

on. Namely, in this case, bind().

(As a comparison, if apply() was replaced by its close cousin, call(),

which takes more traditional looking arguments, it would look like this:

bind.call(fn, fn, 4, 5))

fn, 4, 5 gets passed along to bind(), where fn becomes the this argument

for bind(), providing the scope, and the 4, 5 get bound as the arguments of

the function that bind() is being called on (in our examples, add()). And so

we get the add() function back, but with all its arguments already bound,

ready to be evaluated with a flick of our ().

Memoization

All of which is great, but what’s the point if you have to evaluate the function every time it’s called? Wouldn’t it be better if the function ‘remembered’ the result, and returned the remembered result the second time it was called rather than evaluating it all over again? Or, to continue the increasingly strained example, I should write the answer down on my piece of paper once I’ve worked it out the first time, rather than having to do the sum every time I need to know the answer.

And that’s memoization, a way of optimizing code so that it will return cached

results for the same inputs. This might get a little more complicated with

functions that have more than one input, but for our little lazyEval function

it’s not all that hard (there’s no arguments at all!):

function lazyEvalMemo (fn) {

var args = arguments;

var result;

var lazyEval = fn.bind.apply(fn, args);

return function () {

if (result) {

console.log("I remember this one!");

return result

}

console.log("Let me work this out for the first time...");

result = lazyEval()

return result;

}

}

Let’s give it a function - a sum that does a little reporting for us…

function sum (a, b) {

console.log("I'm calculating!");

return a + b;

}

And let it rip!

var lazyMemoSum = lazyEvalMemo(sum, 4719340, 397394)

lazyMemoSum()

//=> Let me work this out for the first time...

//=> I'm calculating!

//=> 5116734

lazyMemoSum()

//=> I remember this one!

//=> 5116734

It does the calculation the first time, and every subsequent call uses the memoized result.